Public Relations Campaigns: An Integrated Approach

Student Resources

Campaign Materials

The following examples and templates will allow you to get a head start in planning your first campaign.

Research

Sample Likert Scale Items

Sample Likert Scale Items for Answering PR Questions

- Awareness

- I am aware of X.

- I have heard of X.

- Recall

- I have seen X.

- I recall my friends with X.

- Knowledge

- I know about X.

- I really don’t know

- Interest

- I am really

- I am not interested in X.

- Relationship

- I can relate well to others who have X.

- X does not really see me with X.

- Preference

- If I were to consider it, X would be what I want.

- I like X more than . . .

- Intent

- I intend to purchase X.

- X is not something that I would buy.

- Advocacy

- X is something I will tell others to purchase.

- I have been advocating X for quite some time.

Source: From Stacks, 2017, p. 72

Method for Conducting Surveys

1. Write a research question (establish what you need to learn).

2. Review the literature and develop a hypothesis (what you think you might find). Example: People who like us on Facebook will have the most positive opinions of our cause.

3. Select the public or sample “universe.”

4. Decide on the format—online, phone, mail, in-person, and so on.

5. Plan the arrangement of question topics—nonthreatening questions, threatening questions (items about possibly embarrassing behaviors), and demographic data (age and income questions are sometimes threatening).

6. Write questions.

7. When you write questions about nonthreatening topics, remember the following:

- Use closed-ended responses (such as Yes/No or 1, 2, or 3) for responses that tabulate quickly.

- Use open-ended responses to get a range of data and bring up ideas you had overlooked.

- Make questions and responses specific. Avoid double-barreled answers.

- Use terms everyone can understand; avoid jargon.

8. When you write questions about threatening topics (things such as drinking, drug use, or gambling, that might embarrass respondents if they talked about them openly), remember the following:

- Create an environment that lets people comfortably respond

- Prefer open-ended items that let people decide how to respond.

- Include necessary qualifiers and context in questions.

- Avoid technical terms.

- Phrase your question in terms of “most people you know.” People are usually more willing to talk about others than themselves.

- Ask about past behavior before you ask about present behavior.

- Keep questions about deviant behavior in clusters with related items about deviant behavior.

- Put threatening questions toward the end of the questionnaire.

- Answers to threatening questions may be lies.

9. When you write questions to test knowledge, remember the following:

- Ease into items (e.g., do you happen to know?). Don’t make the questionnaire seem like a test.

- Simplify questions and answers.

- Leave questions with numerical answers open-ended.

- If you ask yes/no questions, use related questions later to double-check responses

- Do not use mail or online questionnaires to test for knowledge.

10. When you write opinion questions, remember the following:

- Be very specific.

- Use close-ended responses.

- Keep the affective (feeling), cognitive (thinking), and action aspects in separate questions.

- Gauge the strength of responses by providing a response scale (e.g., how important is this issue to you? Very important, somewhat important, etc.).

- Start with general questions and then move to specific questions.

- Group questions with the same underlying values.

- Start with the least popular proposal.

- Use neutral terms (e.g., the president, not President Smith).

11. Write questions so answers will be easy to tabulate.

12. Consider question order and possible order bias.

- Keep like questions together.

- Start with nonthreatening items.

- Ask demographic questions last. They can be considered threatening.

- Diagram questions in a flow chart to see the logic.

- Don’t make your questionnaire too long. (Some topics may require many questions, but dropout rates increase with questionnaire length. Therefore, you may need to ask priority questions near the beginning of a long questionnaire to increase the likelihood of getting responses to those items.)

- Start with general questions and then go to specifics.

- Go forward or backward in time, but don’t jump around.

- Reverse scale order in some items to eliminate habitual responses.

13. Format the questionnaire.

14. Pretest the survey with people who know about the study. Adjust questionnaire elements that don’t perform the way you expected.

15. Conduct a pilot test by surveying a small number of people from the public you want to check. Adjust survey elements that don’t perform the way you expected.

16. Initiate the full-scale survey.

From APR Study Guide, University Accreditation Board, (2016), 35, https://www.prsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/apr-study-guide.pdf

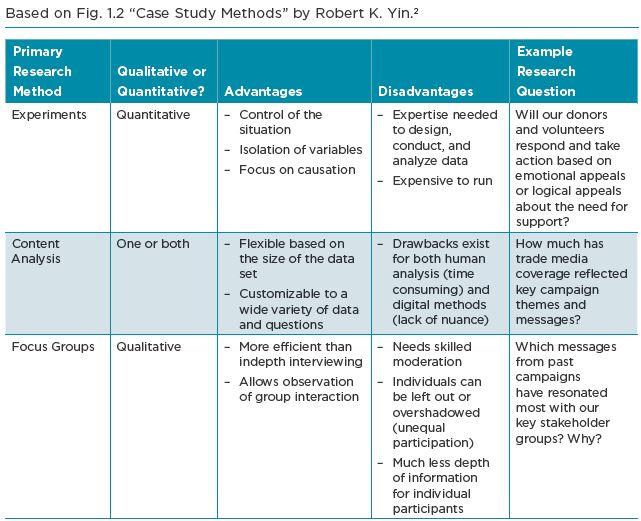

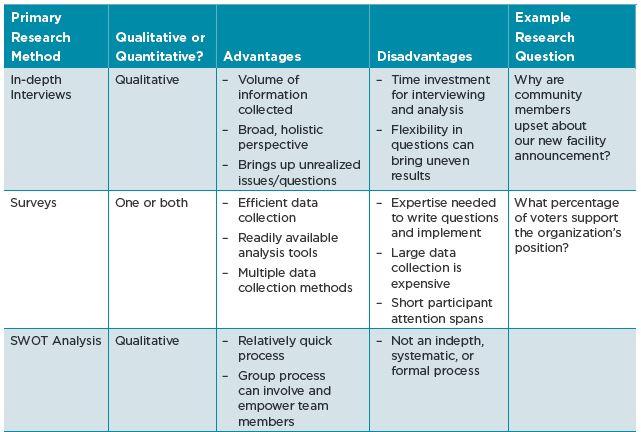

Matching the Question with the Method

When performing research, practitioners should follow the question at hand to help determine the best research method to apply. Methods can serve exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes. Exploratory approaches often answer open-ended questions, attempting to understand fundamental elements of a particular situation. Descriptive approaches seek to provide additional detail about the factors of a more specific situation or phenomenon. By contrast, explanatory research examines causal factors to better understand what might be motivating individual or group behaviors or opinions.1

- Who? Questions about publics and audiences can take many forms, including the examination of secondary research on demographic groups or publics, primary research using social listening tools, as well as qualitative and quantitative interviews and surveys.

- Example: Who are the opinion leaders in a particular community?

- Method: Secondary research on community leadership, dialogue, and demographic trends

- Method: Interviews with and/or surveys of community members

- Example: Who has discussed our company/brand/organization on social media in the past?

- Method: Primary, quantitative, and/or qualitative content analysis, social listening

- Example: Who are the opinion leaders in a particular community?

- What? These questions can either be exploratory (“what have we learned from . . . ”) or more specific and enumerable (acting in place of “how much . . . ?” or “how many . . . ?”).

- Example: What did our organization learn from opening our new branch location?

- Method: Exploratory qualitative interviews and/or surveys with multiple audiences to examine the event from multiple perspectives

- Method: A case study approach (combine the interviews with analysis of internal and external documents, media coverage, and social media conversations)

- Example: What impact has our product made for our customers?

- Method: Interviews or surveys (ideally qualitative and quantitative) to capture the broad range of potential insights and experiences, as well as to provide quantitative data generalizable to all customers

- Example: What did our organization learn from opening our new branch location?

- Where? Secondary methods are often the best starting point, although there are increasingly digital tools to track and identify the location of audiences.

- Example: Where do our customers and potential customers live and work?

- Method: Using social listening tools to track the locations of users and potential customers (when possible)

- Example: Where should we focus our resources for expansion?

- Method: Demographic studies can help make the case for entering a specific geographic market (for example, finding a city with similar socioeconomic makeup or similar cluster of industries to expand your organization’s outreach)

- Example: Where do our customers and potential customers live and work?

- Why and How? Qualitative approaches are often most effective at providing the holistic, detailed answers needed to begin to answer why and how research questions. Quantitative investigation often serves as a secondary step once researchers have initial perspectives and direction.

- Example: Why would community members donate to other nonprofit organizations rather than ours?

- Method (Step 1): Qualitative interviews with key informants inside and outside of the organization to assess potential factors

- Method (Step 2): Based on the initial findings, quantitative survey to isolate both demographic factors among these audience groups as well as to gain additional insight into their behaviors

- Example: Why would community members donate to other nonprofit organizations rather than ours?

Example Methods and Research Questions

Focus Group Moderator Tips

- Warm up the conversation: A smooth, clear introduction sets a professional tone and lays out the goals for a successful session.

- Order matters: Structure the most important questions in the middle of the session, leaving less critical concepts to the end.

- Be positive but nonpartisan: An impartial, business-like approach is best.

- Get everyone involved: Don’t let one or two participants dominate—call on others who look they have something to say.

- Agreement is positive, but avoid groupthink: Encourage participants to build off of each other’s ideas but acknowledge outliers and encourage different perspectives.

Defining Key Audiences, Stakeholders, and Publics

Once some of the initial questions have been answered, practitioners must define who will be impacted by the situation at hand. These may be organizational audiences, individuals and groups who come into contact with organizational campaigns, messages, and spokespersons. Stakeholders can be defined as individuals who can have an impact on the ability of an organization to meet its goals or have an interest in the corporation’s success.3 Organizational audiences include internal stakeholders (such as employees, the board of directors, and stockholders) as well as external stakeholders (such as customers, potential customers, competitors, and vendors). They can also include publics (such as community members). Audiences are defined by the organization, while publics are (as explained by the Situational Theory of Publics) self-organizing around issues, based on their recognition of a problem, recognition of constraints to solving the problem, and their degree of involvement.4 From a marketing or sales perspective, external communication is about targeting audiences to achieve business objectives such as sales goals. From a purely relational perspective, external communication is about strengthening the bonds with important internal and external stakeholders and publics. An integrated communication approach, led by publics relations, takes into account all of these perspectives when researching, developing, and executing campaigns.

Although the task of identifying key groups may seem daunting, this exercise is most useful with a smaller, specific group to whom specific objectives can be designed, strategies directed, tactics implemented, and messages crafted. Campaigns conducted without research and appropriate targeting may accidentally connect with important audiences and stakeholders, but they are more likely to miss the target.5 Practitioners should remember not to overlook the importance of internal publics, audiences, and stakeholders.

In order to evaluate and pinpoint the relevant audiences or stakeholders, it is important to understand the process for developing a more granular view. The first step can be as simple as working with the leadership team in order to identify the important internal and external stakeholders. The team may then use this information to further distinguish any key characteristics; allowing a deeper profile to emerge. Completing this exercise may result in more, fewer, or the same number of audience groups; however, it does provide a starting point to the larger team for developing a better understanding of the organizational view of its position within the marketplace, as well as its internal and external communication challenges and opportunities.

More importantly, the smaller size and inherent commonality of each subgroup allows an organization to listen more closely to these publics and engage in true, two-way communication. Awareness of any issues or challenges can impact campaign and organizational strategy at the highest levels. Companies often have a strong understanding of some key audience groups but are not fully able to see the complete picture. The following are a few common challenges relating to properly defining key audiences, stakeholders, and publics:

- Organizations often focus obsessively on sustaining their current customers, members, or donors, at the expense of seeking and understanding opportunities for expansion and growth in new markets.

- The opposite problem is also common: organizations may direct all of their resources and attention toward acquiring new customers, members, or donors. Current customers may be left without clear, ongoing communication.

- Organizations may not be wholly aware of activist groups or other organized publics who may see the organization, its business, or its structure as a threat.

Even with these same communication strategies at their disposal, far too many PR campaigns are initiated as an attempt to address a perceived need from an organizational perspective: “Our customers are unhappy, so we must communicate with them in a different way,” or “These groups don’t know about our products. If they did, they would buy them!” While this approach may identify an organizational gap, it does not help to find the root of the problem. What research can provide is a roadmap to the solution; the approach to turn the problem into an opportunity.

Content Analysis

Depending on what is appropriate for the situation at hand, the necessary media materials that require review could range from a complete analysis of all media coverage pertaining to an organization over a particular time period of interest, to a much narrower slice of coverage in trade journals on a specific issue or product. Regarding social media, this could include a review of a content and commentary on a specific social medial channel such as Twitter or event-focused research covering multiple social media channels. Social and earned media can and should be reviewed together to generate a holistic picture of public conversation on a specific topic or issue.

Paine highlights multiple categories that can be valuable to track, including prominence, visibility, tone, sources mention, and messages communicated.6 As an example, a campaign developed to raise the profile of a specific product could examine the entire portfolio of company media coverage for a specific subset of media (audience targeted) and then evaluate how prominently product-specific messaging was a focus of given articles. Based on this baseline research, the practitioner can establish a measurable objective—increasing the frequency (percentage) of inclusion or its prominence within coverage—and devise strategies to ensure that outgoing paid, earned, owned, and social media messages reflect this shift. Tailoring for specific metrics can ensure that each campaign is measuring the correct combination of channels and variables in order to both create reliable baselines and track success.

Media Coverage Analysis. One of the more valuable places to start when initiating research on a new project is to conduct media analysis on the specific organization, challenge, or industry in question. This specific type of content analysis can be conducted either quantitatively or qualitatively, formally or informally. By using digital tools to help in the analysis, it can be easy to catalogue data or trends from the time period of interest. This is important in understanding how a specific issue has been framed and reported, which journalists are interested in the topic, and how much media coverage the topic has historically received.

As an example, consider a technology company interested in launching a new application for serious at-home cooks. In order to understand the relevant opportunities for earned media, paid media, and social media, an organization could research specific recipes, ingredients, and techniques that best fit a desired demographic profile from a variety of food-related websites. They might then select the top five websites/media outlets that support the key factors that they have researched and further investigate all associated articles, authors, and topics that appear most frequently. By following this approach, an organization can compile large amounts of quantitative data that support the subsequent planning stages of objective creation, content and messaging development, and audience demographics. Additional qualitative analysis could help to determine questions of tone, article structure, newsworthiness, and target journalists for media relations outreach.

This type of analysis requires a certain degree of pretesting to develop the appropriate scope. For example, searching publications and periodicals that specifically serve the target audience using a defined set of key terms can provide valuable insights regarding an acceptable approach to outreach. Narrowing the research down to the most relevant terminology (as defined by the publications) and the most relevant publications (as defined by the terminology) ensures that deeper, more time-intensive research is time well spent.

Survey Development

Survey questions. As part of survey construction, researchers construct scales—sets of questions or items—that address a particular concept or attitude. Often, such questions will be constructed on a “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” continuum known as a Likert-type scale. Likert-type scales always have an odd number of responses to allow for a “neutral” answer.

Additional options include open-ended questions, multiple-choice questions, and ranking answers.7 Open-ended questions (often including an empty response box, for example) are not conducive to easy quantification but can add depth and nuance to understanding a particular issue. Multiple-choice questions can be valuable for illuminating the potential causes for a particular challenge, the value of certain solutions, or the resonance of particular messages. Including an “other” option is a useful way to gather information that falls outside the researcher’s initial conception of the answers. Finally, ranking answers—asking respondents to order a set of answers in a particular order (best-to-worst, most likely to least likely, etc.)—can be a valuable method for understanding the relative importance or benefits of certain concepts, messages, or potential actions.

Types of survey data collection. There are several methods through which survey data can be collected, dependent on the type of respondent and type of information at hand. For example, a survey looking to capture public opinion on a statewide ballot initiative will be most generalizable, credible, and efficient using a short telephone survey and professional callers. Surveys of existing customers or donors would be least invasive (and most truthful) when done privately and confidentially through a digital survey tool such as SurveyMonkey or Qualtrics. Examinations of specific communities for nonprofit campaigns and outreach—particularly when publics may have limited access to technology—may be accomplished most effectively through personal intercept interviews, where the survey team collects responses in-person. These often work best in high-traffic public places that reflect the survey’s purpose, such as malls, libraries, or community centers. Digital and telephone surveys are most effective for collecting large amounts of data quickly, but phone numbers and e-mail addresses can be difficult and expensive to collect.8 Personal interviews can provide the greatest depth of information and access to difficult-to-reach populations but take significant resources and training to implement. Mail surveys are still used widely but are increasingly being replaced by digital alternatives with higher response rates, significantly faster data collection, and nearly instantaneous analysis tools. That said, mail still may be a reasonable choice for select publics, demographic groups, or geographic locations. With all methods, practitioners should focus on increasing response and completion rates by having concise questions and regular follow-up.

Sampling vs. census. When conducting surveys, researchers must enter the domain of sampling: gathering data from select respondents to represent the whole. By contrast, a census is a universal sample. Practitioners may also, depending on the circumstances, choose a random or probability sample of a given population, or a nonprobability sample.9 Probability samples allow generalizations to be made about the entire population at hand, while nonprobability samples only have statistical validity within the respondents.10 There are many advantages to a census approach when available, including procuring specific information, rather than having to extrapolate estimates from smaller sample sizes. However, a true census requires contacting each and every member of the identified group, which is often extremely difficult and a time consuming, expensive, and inefficient approach.11 Some audiences are easily accessible and conveniently available at the same time. This might include taking advantage of a gathering of company shareholders at an annual meeting, reaching out to employees during a work retreat, or customers at the point-of-purchase.12

Objectives

How Not To Write Objectives

There are multiple approaches that we have highlighted to aid in the development of valuable objectives, but it is also valuable to examine what not to do through ways objectives

can be poorly written.

- Does the measurement matter? (Output-based rather than outcome-based):

- A variety of metrics have been used in the history of PR to keep pace with a data-driven business world and to gain leadership buy-in relative to the marketing and advertising functions. Unfortunately, many of them have been based less on impact and more on measurement methods including ad value equivalency (AVE), or counting the number of media clips rather than looking at their value.13 The 2010 adoption and subsequent 2015 revision of the Barcelona Principles for PR Measurement explain that AVE and clip counting are not valuable objectives as they do not directly relate to organizational goals.14

- Examples:

- Original (output) objective: Place seven media stories in targeted industry publications prior to a January event.

- This objective is easily measurable but not based on an audience outcome.

- Revised (outcome) objective: Drive web traffic (1,500 visitors) to the registration page for a January event among key industry audiences.

- This objective is both easily measurable and clearly focused toward the organizational goal of event attendance.

- Strategies for executing this objective may include media relations outreach with stories including a link directly to the registration page

- Original (output) objective: Place seven media stories in targeted industry publications prior to a January event.

- Is the objective primarily communication driven? (Not tied to public relations efforts):

- Public relations objectives can be sidetracked with shared objectives, specifically those relying on the outputs from another department. This can happen with sales and marketing, human resources, events, membership, fund-raising, and many other functions within the organization. Organizational goals and objectives at the highest level can often only be achieved when departments work together. The development of appropriate public relations objectives improves the outcome and cohesiveness.

- Examples:

- Original (multidepartmental) objective: Increase employee retention by 15 percent over the next year.

- This objective relies on multiple factors outside of communication efforts. The human resources department may not be supportive of the initiative or have any resources that support or justify communication efforts on behalf of this objective.

- Revised (communication-specific) objective: Increase employee awareness of a new benefits package from 30 percent to 60 percent over the next six months.

- This objective focuses on awareness and information distribution within the scope of what communication can accomplish.

- While the revised objective may not solve the entire organizational challenge, it does tackle a communication-specific piece of the retention puzzle. Continued cross-functional cooperation during the planning, implementation, and evaluation phases of the campaign would ensure a coordinated effort toward the larger objectives.

- Additional communication objectives working toward a similar organizational objective may include those related to a change of opinion about the employer, development of new internal communication tools, or even new channels to improve the flow of information within the organization.

- Original (multidepartmental) objective: Increase employee retention by 15 percent over the next year.

- How much impact will come from achieving the objective? (Not closely related to organizational goals):

- Objectives can be extremely well written, clear, and measurable, but not relate closely enough to organizational priorities. This may include a media relations effort that does not result in on-message coverage, campaigns that do not adequately prioritize the audiences they target, as well as disconnections between short-term and long-term objectives.

- Examples:

- Original objective: Increase awareness of consulting services for existing clients from 50 percent to 75 percent over the next six months.

- If the organizational priority is to target new clients with consulting services, rather than existing clients, it doesn’t matter how effective they are at exposing existing clients to this information.

- Revised objective: Capture contact information from 20 potential clients interested in consulting services over the next three months.

- The revised objective measures an opt-in behavior on the part of the potential client, rather than awareness, as well as focusing on new clients rather than existing clients.

- Strategies for this approach could include internal and external research as needed to define the ideal new client; targeted awareness efforts using paid, earned, shared, and owned media; as well as a lead-capture strategy such as a dedicated landing page as part of a website or blog.

- Original objective: Increase awareness of consulting services for existing clients from 50 percent to 75 percent over the next six months.

- Is it organizationally feasible? (Not enough enthusiasm, time, or resources to complete the effort):

- Some objectives may be ideal from the perspective of the public relations team but not the best approach for other areas of the organization. This situation can cause significant internal conflict and divert the resources and energy needed to accomplish the goal. Of course, the more organizational clout the public relations department or agency carries (usually earned through prior success), the better chance that they have of bringing other departments and executive leadership around to their position.

- Examples:

- Original objective: Increase awareness of a new type of mortgage loan product among targeted prior customers from 15 percent to 30 percent in the next three months.

- Unfortunately, the objective starts at the same time as a new regulatory measure comes into effect, taking up significant time for the loan officers who would have spearheaded the outreach.

- Revised objective: Increase awareness of a new type of mortgage loan product among targeted prior customers from 15 percent to 30 percent in the next six months.

- As the new mortgage loan product was not revolutionary, simply new to the company, communicators may recommend that the campaign could either begin later or be spaced over a longer period of time to ensure key internal stakeholders were able to fully participate.

- The objective can also be revised to lower the measured change, assuming that loan officers would not be able to participate.

- Original objective: Increase awareness of a new type of mortgage loan product among targeted prior customers from 15 percent to 30 percent in the next three months.

Strategies

When to Not Use Social Media

While the overwhelming narrative is that organizations must use social media constantly, it is easy to find examples of when not to use social media as part of strategic campaigns. In 2013, communicators at JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States, used the @JPMorgan handle to tweet, “What career advice would you ask a leading exec at a Global firm? Tweet a Q using #askJPM. On 11/14 a $JPM leader takes over @JPMorgan.” The strategic transparency backfired when JPMorgan Chase, a company that had been heavily implicated in the 2008 financial crisis and had recently suffered criticism for significant losses due to exceptionally risky stock market trades, received an avalanche of negative tweets from hundreds including disgruntled consumers and opportunistic reporters. A New Yorker article recapping the incident put it succinctly: “This is Twitter’s very purpose: to allow any individual to share the same space with, for example, a hugely powerful bank. . . . Unlike at JPMorgan’s Park Avenue headquarters, there are no security guards keeping undesirable elements out of Twitter.”15

While organizations may control the initial message, any response is out of their hands. In this way, social media strategies carry inherent risk. The rewards of a successful campaign often clearly outweigh such risks, but it is a calculation that communication team members should make based on thorough analysis and understanding of the organization and the publics involved. Practitioners should ask themselves and their colleagues, “what is the worst thing that could happen?” before undertaking strategies on potentially challenging subjects.

Review: Positioning Campaigns for Maximum Impact

Uniqueness

Whether it’s a channel, a message, or the strategy itself, finding a way to make it new or distinctive will always add value. A story can become more newsworthy, an event can become more attractive for potential attendees, and a member donation can be made more impactful. Uniqueness is often found when organizations act the opposite way from how their audiences expect them to.

That said, content, programming, or campaigns need not be wholly new to reap the benefits. It can be new for a region, new to an industry, or new to a company. It’s the degree of difference from expectation or from competitors that defines its value for a given audience. This holds both for the impact to a reporter (news value) as well as the impact on an organizational stakeholder.

Audience Focus

If a strategy is not right for the audience, it doesn’t matter how big the budget, how bold the message, or how well-timed a campaign might be.16 At the strategic level, practitioners should consider how the audience perceives the organization or the issue at hand, how that perception must change to achieve the goal, and what the best avenue might be to facilitate that change. What does your audience need to hear to move the needle toward completing an objective? Where are they listening? When are they most likely to hear and understand your message? If a strategy clearly addresses all three of these questions, it is well on its way to being effective.

Playing to Your Strengths (and Competitor’s Weaknesses)

It is a truism in advertising, marketing, and sales: trumpet your advantages over competitors. Once you have pinpointed the areas of distinction, often through SWOT analysis, it allows communicators to choose strategies and messages that effectively reinforce them. These differences could be communication-related, such as expertise and resources devoted to managing and monitoring social media channels, or it could be company-, product-, or service-related, such as having a highly regarded industry expert on staff. This knowledge could inform strategies across a variety of channels impacting the campaign, such as content creation and distribution (expert white papers or bylined articles), media relations (expert source for reporters), or events (expert speaking opportunities). Even channel-specific advantages can support multiple strategies. A superior social media team can strengthen real-time customer interactions during an event, while improving the impact of earned media placements through additional sharing and promotion.

Tactics

Types of Advertising

Outdoor. Outdoor advertising, traditionally dominated by print billboards that are located on or near highly trafficked roads, provides cost-effective advertising options for organizations. Both standard, highway-sized billboards and smaller junior billboards are generally purchased for a defined period of time (by the week or month), allowing for effective audience repetition and awareness for organizations and their events, products, or announcements. As some communities see billboards as unsightly, there are many local restrictions on their size and placement, making it difficult to blanket a community in the way that broadcast advertising can. Billboards are often purchased through national firms with availability in all major markets.17 Beyond traditional billboards, transit advertising (such as on buses and trains), building signage, and digital billboards can all offer additional flexibility and target different audiences.

Print. Traditional newspaper, trade publication, or magazine advertising focuses on specific audiences bound by geography, profession, or interest much more clearly than broadcast media. There are multiple types of newspaper advertisements. Display advertising includes large, often image-driven ads scattered throughout the publication. By contrast, classified ads are smaller, organized by content, text-heavy, and contained in a specific section.18 Print ads are generally measured in inches and priced by size, color, location, and audience. As a prime location, the back cover of a magazine, for example, is often much more expensive than inside pages. Overall, rates are often driven by the type of audience as much as its size: a publication that targets high-income consumers or business executives will often charge more for the same advertisement than one that has a lower-income or less influential readership.

Radio. Similar to television, traditional broadcast radio stations often carry a mix of local and national content based on their format (news/talk, music, community/public radio, etc.). As commuters are the primary radio listeners, the most expensive periods for advertising are during drive time: the morning and evening commutes of local residents. Listeners often tune in daily to the same radio personality or channel, creating a more reliable audience than other media.19 While alternative distribution channels such as satellite radio, digital live streaming, and podcasts continue to grow, the majority of advertising opportunities are still found within traditional over-the-air broadcasts.

TV. Television advertising starts with the relatively high cost of both creative production (the ads themselves) and air-time (the duration, frequency, and location where they appear). With that in mind, there is significant variance between relatively inexpensive local network affiliate advertising, regional or national cable advertising, and national network advertising. Ads within a program are called participating program announcements, or participations. Longer-form ads that resemble programming

are called infomercials.20 When purchasing TV ads, discounts are available given quantity and frequency. Airtime during primetime evening programs is the most expensive.

Digital Display. Digital display ads come in a variety of formats, from the ubiquitous pop-ups to website banners; each with continuously evolving targeting and richness. Such ads can be directed based on a combination of the context of the content, user behavior, geography, time of day, and numerous other factors.21 Advertisers are working to balance the robust capability of these ads to include attention-grabbing animation, sound, and other features, with the potential for intrusion and annoyance of the audience.

Search Engine Marketing (SEM). Paid advertising directly to search engines, such as Google or Bing, allows organizations to have ads served to potential customers, members, donors, or supporters based on specific search terms, demographics, and geographic factors. It is the most popular form of digital advertising.22 Distinct from organic search and search engine optimization (SEO), paid SEM results in advertisements set apart from the organic results. Tools such as Google AdWords allow organizations to create highly customized, flexible, and scalable SEM campaigns for targeting their audiences. Rather than a negotiation method to purchase ads, used in most other formats, SEM uses a bid format based on the popularity and competitiveness of the keywords.23 Such functionality makes SEM complicated to execute effectively, which can be a barrier for many small organizations.

Social Media. Paid social media outreach or advertising is another growing area available to even the smallest organizations. The detailed information available for each individual user allows for very specific targeting and efficient paid outreach. There are a variety of paid options available on many different social media channels; ranging from boosting existing content—paying for additional reach on organizational posts or events—to display and banner advertising. While Facebook and other platforms reward conciseness and visually compelling ads (rather than text-heavy content), research has shown that “informativeness” and creativity are critical drivers of consumer action for advertising on social networking sites.24 To be informative, ads must give audiences the relevant information they need and expect. Creativity in this context captures attention both through the approach as well as the design and structure of the advertisement itself. Tactics can range from a variety of message strategies (i.e., functional appeals, emotional appeals, or comparative appeals) to promotions (i.e., sweepstakes, discounts, and special events), and user-generated content (i.e., submission contests, engaging surveys, or other brand engagement activities).25

Event Sponsorship. An opportunity to connect with professional networks or large community groups fuels investment in event sponsorship. There may be large discrepancies in pricing between becoming the named sponsor for an entire regional music festival or sponsoring snacks at the mid-afternoon break of a local professional conference. Organizations should tailor event-related opportunities to their budget and, as much as possible, to the themes and messages they are trying to convey. Event coordinators often have broad flexibility to customize sponsorship opportunities based on budget and organizational needs. That said, companies can be competitive in jockeying for position at key events, so locking in sponsorships early is always recommended.

Media Relations Tools

Media Advisories. Media advisories are invitations for media to cover a specific event scheduled for a defined date, time, and location. Any advisory should include (in a list rather than paragraph format) what the event is, who will be taking part, when it will take place, where it will take place (either geographically or digitally), and why it is newsworthy. Leveraging media advisories can be particularly useful for campaign events where a broad range of journalists may be invited. They should be concise but clearly outline why a reporter would want to attend. The hook is often about the experience that can be captured as much as the news value of the information being shared.

Press Releases/News Releases. The ubiquitous press release or news release, while often considered out-of-touch in a world of increasingly customized media outreach, can still serve as a highly effective outreach tool. Howard and Matthews describe the press release as “a for-your-information memorandum to an editor.”26 Like a memo, the information contained within a press release should be concise, while also answering the major questions a journalist might have about the announcement. It should provide a basic grounding from which a reporter can further research and gather information for a story. Most importantly, such an announcement must contain genuine news. A press release without news value is as appetizing for reporters as being offered a sandwich and receiving two pieces of dry bread. Practitioners should understand the value in a release before they send it out and only share it with reporters who would appreciate that news value for their beat and their readers.

Press Conferences and Media-friendly Events. Despite the reduction in media resources to cover news stories, media-focused events can still be a useful tactic to gain coverage and support other strategic objectives. Events cultivate relationships with key audiences, provide information, and can be much more engaging and immersive than a press release. That said, the days of holding a press conference for every major corporate announcement are long gone. Practitioners should always ask themselves what an event would add to the story for a reporter. Why would it be more effective than a traditional announcement? Would the event still be a success if no reporters attended? What content

(images, video social media posts, narratives, etc.) could be captured during the event for future use? Do I have the budget to achieve the event’s goals?

When planning events with the media in mind, it is important to consider what would make it convenient and valuable to cover, such as timing, visuals, and community relevance. In some cases, these questions may point to a staged media event with relevant speakers. If the news value is high enough, a full-scale event may be the best fit. If not, a media conference call with key parties may be able to address the same media needs and be more efficient for everyone involved. Reporters should be sent invitations to such events well in advance, as well as reminded as the date of the event approaches.27 A media advisory (see description above) is designed specifically for this purpose.

Bylined Articles and Op-ed Pieces. Many practitioners underestimate a media outlets’ willingness to accept and publish submitted content. When organizations have something to say, be it a clear position on a topic, an insight to share, or a point to drive home, opportunities such as op-ed pieces and bylined articles become a useful tool. An op-ed, short for opposite of the editorial page, is a focused, single-issue perspective piece designed for a general audience.28 Bylined articles, often accepted by industry trade publications, can provide a look inside the successful strategies, unique decisions, or innovative technologies. The most effective bylines for both journalists and a publication’s audience are educational and informative rather than self-serving for the author’s organization.

For example, a company opposed to a piece of state legislation may gain added publicity and credibility, as well as influencing the debate at hand, a thoughtful 500-word essay from the CEO explaining the potential challenges of such new laws. Hundreds of local and national op-eds are published in the United States every day. Alternatively, trade publications appreciate bylined articles that provide insight into processes, innovations, trends, or controversies within that industry. With a new technology, product, or process, it may make the most sense to have an article with the VP of Engineering’s byline, while a story focused on the organization itself may have more value coming from the CEO. It is particularly important to find the right degree of technical language for an industry audience, particularly as an outside agency practitioner. Often, the slow process of reading multiple industry publications and asking many deliberate questions about terminology can bring communicators up to speed.

Shared Media

Blogs: An Organization’s Content Hub. The center of social media outreach is the idea of blogging; individuals sharing their ideas with anyone else in the world who stumbles upon them. Organizations should consider one central point of information for their digital presence and organize around it.29 Often, this job is done by a blog or blog-like part of the organization’s website. The ability to post original or curated content and solicit public feedback through comments and discussion are the foundation of Web 2.0; or the social web. This major advance made interactivity accessible to those without knowledge of programming languages and made the Internet a significantly more potent force for (and sometimes against) public relations practitioners.

Many different types of blogs exist, both in form and function. The most traditional (such as many hosted on sites such as Blogger and WordPress) feature a single author or core group of authors, a key topic or theme, and a regular posting schedule. The blogger owns and controls the main content on the site, although he or she usually allows and encourages interactivity. At the other end of the spectrum are the micro blogging sites such as Twitter, where content length is limited, and the conversational space is shared among the user base. Social media sites such as Facebook and LinkedIn are found somewhere in between and include different forms of blogging within their functionality, as well as channels such as YouTube and Vimeo that allow the creation and sharing of (among other types of multimedia) video blogs or vlogs.

Organizations can use blog tactics as the centerpiece of a content creation strategy: a content hub. It could include traditional press room content (company news and press releases, executive bios, and photographs, as well as basic company background and content information) but also feature a variety of voices, such as employee and customer posts, and perspectives from different geographic or departmental areas. The audience includes both internal and external publics, including potential employees, customers, and community members.

Social Media Networks. Social networking allows organizations to connect, share information, and listen alongside potentially millions of customers, fans, or supporters. It gives organization’s the privilege of speaking directly to this audience and audience-members the opportunity to speak back. Safko notes that, because of this delicate relationship, social network content should not be a place for selling but for building brand loyalty through sharing useful and interesting information.30

While many networks exist, two in particular have added significant value for many organizations: Facebook and LinkedIn. As the largest social network, Facebook has significant reach to both broad and highly targeted groups of individuals. Organizations can manage their pages to share content, create events, capture contact information, point users toward a website, and develop a base of followers resulting from page likes. Both organic and paid tactics are useful for increasing exposure to key audiences and drive engagement as part of campaigns. Successful outreach requires a long-term content strategy, including multimedia, and an understanding of what your organization’s audience will find both readable and shareable. As Facebook is considered a personal social network, its content tends to focus less on business-to-business and more on consumer products and services.

LinkedIn, by contrast, functions for many users like a rolodex; a listing of individuals and their job histories. Many organizations have also taken advantage of the network’s underutilized sharing and connectivity functions. As part of campaigns, LinkedIn can be a valuable place to share content. As a professional network, LinkedIn provides an avenue for conducting business-to-business conversations and networking, improve job skills, or career advancement. While LinkedIn may not necessarily be a fit for every campaign, many could benefit from its reach.

Microblogging. Twitter is the clear microblogging leader with more than 320 million monthly users as of March, 2016.31 Microblogging can be particularly effective for expanding coverage, engagement, and digital participation in campaign events, as well as to connect with key influencers or constituencies. Organizations can feature a variety of relevant content, including retweeting important information, starting public conversations about issues, and linking to organizational content, including blog posts. Since Twitter is largely public and searchable, it can serve as a useful listening tool as well. One downside of engagement is that it requires organizations to post content consistently in order to be impactful. Organizations must evaluate whether the investment required to create and manage the content will be sustainable for the length of the campaign.

Hashtags allow organizations to enter or create conversations around events, campaigns, and other interest areas.32 By considering relevant, concise hashtags, practitioners can more easily drive conversations among those interested in specific topical content.

Image, Video, and Interest Sharing. A variety of image and video-driven social networks have evolved and added unique functionality to the social sphere. YouTube and Vimeo are the largest long-form video sharing services. As the algorithms for Facebook and other channels continue to prioritize video sharing, these channels will only grow in importance. While the quality of video for shared media does not necessarily need to match broadcast media standards or budgets, practitioners should focus on the quality of their message. As Safko points out, the most important element is “quality content, not quality production.”33 If a cellphone video communicates the message to viewers and captures a shareable, authentic moment, it may be more effective than spending tens of thousands of dollars on professional video production. It is all about the context, message, and, of course, the audience at hand.

Additionally, a wide variety of niche networks have evolved for sharing specific types of content. Each has its own set of customs and should only be used organizationally when the content is a very clear fit with its functionality. For example, many fashion and lifestyle brands have embraced Instagram’s and Pinterest’s cultures of high-quality images, while location-driven brands can take advantage of Snapchat’s geofilters. Live video streaming using Facebook Live and other apps may also be a useful way to share important campaign events with those who may not be able to attend in person. The evolving possibilities of social media mean that practitioners must constantly investigate and evaluate new channels and possible tactics relevant to their organization or clients.

With any social network, establishing an audience is a significant investment of time, effort, creativity, and oftentimes, financial resources. As campaigns are time-bound and budgeted, practitioners must prioritize the channels for interaction based on where audiences already exist. Put simply, an organization would be better served to focus additional campaign resources to support their strong, active Facebook following, rather than branching out into new networks, even if the content may be a strong fit for Instagram or Pinterest. With that being said, campaigns can also be an opportunity to expand an organization’s social media presence, particularly when it is done logically and with a long-term focus.

Community Management. Social media community management should be an ongoing activity for organizational communication, but it can also be integrated into campaigns as a tactical approach. AudienceBloom founder and CEO Jayson DeMers defined community management, distinct from social media channel management, as “the process of creating or altering an existing community in an effort to make the community stronger.”34 Communities, whether based on organizations or interest, can be extremely valuable groups to tap or empower as part of campaign tactics. Such tactics must be managed carefully to ensure that information shared is valuable to the community and not just to the organization. Communities have specific rules, and campaign tactics should only include them if the organization or its members, staff, or other stakeholders are already active, contributing participants.

Whether sharing content or managing communities for a campaign, being able to listen is also of immense importance. It goes beyond simply turning on and responding to notifications about an organization’s existing channels. Listening comes in the form of following both the broad trends and discussions that happen on relevant social media channels, as well as the evaluation of specific posts, content types, channels, communities, and strategies. Even if sharing content with such communities is not an appropriate step, being a part of the conversation can lead to valuable insights about their conventions, the style and tone of discussions, and the types of messages that resonate.

Owned Media

Website Content Management. Organizational websites are nonnegotiable in today’s business world. They are a foundational piece of credibility and are one of the first places any new stakeholder goes to learn about the organization and to take actions, such as purchasing products, downloading content, or renewing a membership. Campaigns often seek a form of conversion, an action such as buying an event ticket or signing up for an e-mail list, as an objective, and websites are often where such tactics occur.

Organizational websites exist prior to, during, and after campaigns, and integration should support the businesses’ overarching purposes and messages. Campaigns often need a temporary online home as part of this digital presence. This could present itself in the form of a dedicated page or section of the website or a separate microsite that integrates all campaign information and functions; often serving as a place to drive traffic from other digital and traditional channels. Organizational websites also provide opportunities for rotating, newsworthy content as part of their homepage, and campaigns should see this as one significant opportunity to draw in users who are interested in the organization but not necessarily the campaign. Similarly, they can point interested users to dedicated campaign information.

Marketing Tactics. PRSA defines marketing as “the management function that identifies human needs and wants, offers products and services to satisfy those demands, and causes transactions that deliver products and services in exchange for something of value to the provider.”35 Many public relation activities are closely connected to marketing activities and are often underused toward marketing ends. For example, positive earned media coverage should be shared with key organizational publics. This could include integrating the media coverage into paid/boosted content shared via social media channels, e-newsletters, or even traditional printed brochures.

Publications. Organizations develop a wide variety of print and digital publications that serve both to distribute content and provide audiences the chance to browse a wider breadth of stories that they may otherwise not be exposed to. The bar for content creation in such outlets is high since the information must be both valuable and interesting to readers. Publications come in several varieties, including recurring serial publications like newsletters (print and digital), organizational magazines, and annual reports.36 Newsletters and magazines, even in print form, are still a popular form of organizational communication and represent an accessible way to share information both within and outside of a campaign structure. While design and production costs vary greatly, particularly when printing and mailing are involved, many organizations still see the value for member/donor outreach, sales and marketing, and event promotion. Many organizations adapt the content produced for such publications for digital purposes. Digital versions of publications, often distributed via e-mail distribution services such as MailChimp, have the advantage of metrics that track clicks on stories and links. Practitioners can use this information to improve story selection, multimedia content, and writing for future issues. The effectiveness of these publications is dependent on having an up-to-date mailing or e-mail distribution list.

Stand-alone (nonrecurring or nonscheduled) publications include e-blasts, reprints, reports, and whitepapers, as well as brochures and flyers. E-blasts are often used to alert specific audiences about more immediately newsworthy content and are timed around the specific event rather than on a weekly, monthly, or quarterly schedule. Reprints are designed versions of media articles that can be repurposed for print or digital use.37 Copyright law’s fair-use provisions provide for some internal and educational use of reprints, but public dissemination generally must be approved and paid for by the media outlet itself. Reports encompass a variety of documents from public-facing research whitepapers (which can be written and disseminated on campaign-specific topics) to customer or member-focused reports on key organizational issues. Generally, the purpose of such reports is to inform the audience in detail on a specific topic or provide information tailored for a specific time, event, or campaign. Similarly, fewer organizations have a comprehensive brochure about their work, but many have maintained product or program specific brochures. Brochures are made up of folding panels, in contrast to flyers or sales sheets, which often accomplish the same narrowly focused purpose but on a flat piece of paper.38 One advantage to flyers and sales sheets is that they can be printed easily in-house, although the quality, particularly with color images and photos, often suffers.

An increasingly popular format is that of the infographic, which uses a mix of sym-bolic imagery and language to represent specific concepts. On one end of the spectrum, infographics can be built as a more detailed version of traditional charts and graphs or process representations. In the extreme, they tend to lean more toward a heavily icon-centric, image-driven approach. The most effective infographics are usually the product of collaboration between writers and designers, leading to an output that is both rich in information and easy to understand.

Collateral Materials. Additional materials can be developed for both digital and traditional uses, either as stand-alone pieces or as part of a broader event or campaign. These can range from a variety of branded logo items to the trade show booths that will represent the business focus. Organizations often use their own space as a type of collateral, including decorations inside and outside of the building for special events. This can expand to a variety of posters and banners ranging from small easel-mounted foam core pieces to specialty printed banners that take up an entire side of a building. The design should reflect the scope and importance of the campaign itself, always representing the larger brand.